Očuvanje ostavštine hrvatske dijaspore u digitalnom svijetu

Nedvojbeno je da je Hrvatski vjesnik svojim objektivnim izvještavanjem i nepokolebljivim zalaganjem za domovinske principe dao značajan doprinos izgradnji hrvatske državnosti i slobode. Ovaj uspjeh jasno je pokazao snažan utjecaj koji mogu imati dobro organizirane zajednice dijaspore kada su ujedinjene iza zajedničkog cilja.

Piše: Ivo BUTKOVIĆ

Evolucija svake ozbiljne hrvatske političke emigrantske inicijative – posebice one koja je zadržala svoju relevantnost od ranih 1980-ih do danas, u razdoblju od 41 godine – predstavlja značajan povijesni narativni izazov.

Još je značajnija priča o tjedniku koji je u dalekoj Australiji nastao zajedničkim radom 16 različitih hrvatskih iseljeničkih udruga, klubova i političkih društava. Njihova zajednička vizija bila je modernizirati hrvatski državotvorni pokret kroz suvremene medije.

Ova društveno-politička koalicija bez presedana stvorila je tjednik posvećen predstavljanju istinitih prikaza zbivanja u domovini slobodnom svijetu i zajednicama hrvatske dijaspore. Želja im je bila točno prenijeti hrvatske državotvorne težnje i politički razvoj.

Pokrenut iz Australije, tisućama kilometara od domovine, ovaj politički angažirani tjednik predstavljao je istinski revolucionaran pothvat za svoje vrijeme.

Nažalost, početni pokušaj, koji se uvelike oslanjao na starije pristaše Hrvatske seljačke stranke (HSS) u Radićevoj tradiciji, pokazao se neuspješnim. Ovaj rani neuspjeh dogodio se u mračnom razdoblju kada je jugoslavenska državna sigurnost (UDBA) brutalno ubila bivšeg direktora naftne kompanije Ine Stjepana Đurekovića u Njemačkoj 28. srpnja.

Nakon atentata na Brunu Bušića 1978. godine uslijedio je identičan zločin protiv Đurekovića koji je, kao i Bruno, svojim spisima i knjigama razotkrivao jugoslavensku propagandu i neistine. Ovo brutalno ubojstvo potaknulo je i radikaliziralo hrvatsku političku emigraciju diljem svijeta.

U Australiji, najdinamičnija organizacija — tada poznata kao Hrvatski savez Uzdanica – Hrvatska mladež (UHM) — odgovorila je sazivanjem dvodnevnog sastanka u Melbourneu s čelnicima svih ogranaka. Razgovaralo se o doprinosu dijaspore domovini i analizi političke i opće situacije u Hrvatskoj.

Sastanak je uključivao procjenu partnerstva sa savezničkim organizacijama u europskim gradovima, uz obavještajne podatke nedavno pristiglog 'izviđača' iz Europe koji je pojasnio poruke američkih i europskih suradnika.

Sudionici su zaključili da je za promicanje njihove stvari potrebno osnivanje novih sveobuhvatnih hrvatskih tjednika u Australiji, s ambicijama međunarodnog dosega 'preko mora'.

Zbog toga su odlučili ukinuti svoj organizacijski mjesečnik Uzdanica i svoju energiju usmjeriti na razvoj ovog novog tjednika. Nakon ovih i drugih potpornih inicijativa, odlučili su se konzultirati s vlč Josipom Kasićem i uspostaviti kontakt sa Srećkom Roverom.

Grupacija je za glavnog urednika postavila Ivu Butkovića, uz potporu Tomislava Bošnjaka, tadašnjeg tajnika organizacije UHM. UHM bi poslužio kao temelj, uključivši svoje ogranke i članstvo u razvoj i rad lista.

Kako bi unaprijedili ovu inicijativu, osnovali su 'Hrvatsko zajedništvo u Australiji') 'Croatian Unity Australia' strukturirano u skladu s australskim zakonom kao dioničarska, ali dobrotvorna i kulturna organizacija—što znači da se financijska dobit ne može raspodijeliti među članovima, već se može samo reinvestirati u daljnji razvoj u skladu s propisima.

Članovi utemeljitelji 'Hrvatskog zajedništva' bili su: Hrvatsko narodno vijeće MO 'Bruno Bušić' – Geelong, Hrvatski klub 'Kralj Tomislav' – Sydney, Hrvatski katolički centar Clifton Hill, Hrvatske subotnje škole – Broadmeadows, Hrvatski savez Uzdanica – Hrvatska mladež – Melbourne, Hrvatski narodni otpor 'Ante Vrban' Sydney, 'Ujedinjeni Hrvati' – Wollongong, Ujedinjeni hrvatski studenti u Victoriji, i MO HNV 'Hrvatsko gorje'. Kasnije su se pridružila i dodatna hrvatsko-australska društva, uz potporne organizacije izvan Australije, uključujući i jedno iz New Yorka.

Prvi broj 'Hrvatskog vjesnika' pojavio se u hrvatskim institucijama i na kioscima 16. kolovoza 1983. U razdoblju do nedavnog prelaska na digitalni format objavljeno je 2026 tiskanih brojeva, što je izniman i povijesno značajan uspjeh.

Hrvatski vjesnik predstavljao je daleko više od samo još jedne novine u Australiji; utjelovio je moćan pokret koji je proširio svoj doseg na američke i europske zajednice, a potajno se vratio u domovinu. Ovaj uspjeh potvrda je predanosti brojnih hrvatskih klubova, institucija, centara, uredništva, čitatelja, distributera i svakog pojedinca koji je, makar skromno, pridonio Vjesnikovom opstanku u petom desetljeću i evoluciji u digitalni oblik.

Hrvatska domoljubna revolucionarna aktivnost koja je izvirala iz Australije pokazala se duboko zabrinjavajućom za jugoslavensku tajnu policiju (UDBA) i branitelje jugoslavenstva. Tu su inicijativu od samog početka nastojali potkopati i umanjiti, često kroz naizgled bezazlena pitanja poput: “Kada već postoje dva hrvatska tjednika, zašto stvarati treći?”

Tada smo se suzdržali od odgovora otkrivanjem određenih saznanja ili sumnji, a tu ćemo diskreciju zadržati i sada – iako su te spoznaje i sumnje od tada potvrđene brojnim dokumentiranim činjenicama sačuvanim u arhivima. Ove su istine sada poznate mnogima, a posebno ih dobro razumijemo mi koji smo povezani s Heraldom, kako prošli tako i sadašnji.

Primjerice, sumnja da je Krunoslav Prates, urednik lista 'Hrvatska država' (München), “vrlo nestabilna, financijski kompromitirana osoba” nedvojbeno je potvrđena kada je 2007. u Njemačkoj osuđen na doživotni zatvor. Kao suradnik UDBA-e sudjelovao je u orkestriranju atentata na Stjepana Đurekovića.

Na ta tadašnja “zabrinuta” pitanja – zašto osnivati još jedne novine? – prvi broj novog tjednika “Hrvatski vjesnik” ponudio je jezgrovit odgovor: “Zato što postojeće novine nisu zadovoljavale potrebe hrvatskih zajednica u Australiji”. Mi bismo jednostavno dodali: jer su djelovali izvan suvremenih političkih stvarnosti koje pogađaju i svijet i domovinu.

Međutim, prvi broj sadržavao je i opsežniju izjavu odbora 'Hrvatskog zajedništva' koja je jasno ocrtavala politički smjer publikacije — inovativan i po konceptu i po putanji. To se pokazalo eksplicitnim izjavama da su osobe poput Bakarića, Blaževića, Šuvara, Tita i Rankovića, uz četničkog 'vojvodu' Jevđevića, jednako neprijateljski raspoložene prema hrvatskoj suverenosti – zločinci koji su aktivno potkopavali hrvatski identitet i neovisnost. Stav publikacije dodatno je iskristaliziran u snažnoj tvrdnji: “S entuzijazmom smo pratili svaki pozitivan razvoj u Hrvatskoj, kao i danas.

Sve pozitivno od Hebranga do Tuđmana integrirali smo u hrvatski politički mozaik bez ideoloških predrasuda.”

Nakon razotkrivanja jugoslavenskih protuhrvatskih aktivnosti i zavjera unutar Australije, zaključak je nedvosmislen: "Iako ne možemo promijeniti prošlost, imamo moć odlučno oblikovati budućnost. Imperativ je pristupiti povijesti sabrano, dosljedno i precizno. […] Naša je dužnost suprotstaviti se neprijateljskim shemama kroz konstruktivan hrvatski politički i kulturni angažman.

Naša politička ideologija je destilirana na ovo: uspostava najveće, najsigurnije i najtrajnije hrvatske države! U ovoj fazi naše borbe za slobodu nemamo stranačkih predrasuda. S poštovanjem pozdravljamo različite hrvatske perspektive na ovim stranicama, pod uvjetom da su u skladu s državotvornim načelima i, nedvosmisleno, s antijugoslavenskim etosom.”

Pregledom analiza i političkih kolumni, bilo prošlogodišnjih ili ranijih godina, nema sumnje da je Hrvatski vjesnik (HV) ostao pri stavu iznesenom u prvom broju iz 1983. godine. Postoji puno povjerenje da će ova tradicija ustrajati u svojoj novoj digitalnoj inkarnaciji.

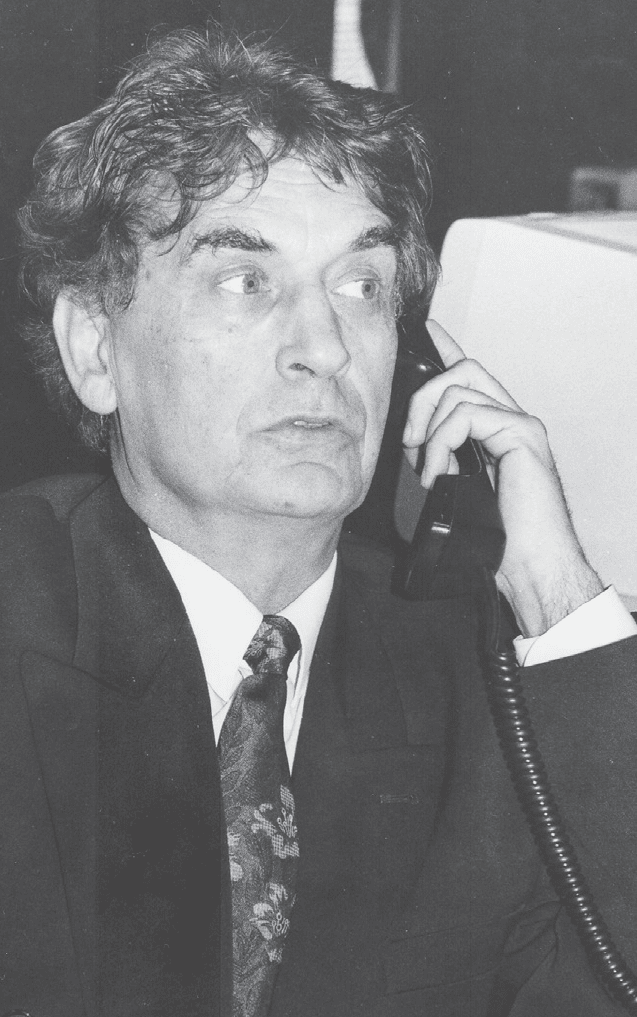

Primarne zasluge za ta postignuća pripadaju četiri glavna urednika publikacije: Ivi Butkoviću (1983. – 1991.), Tomislavu Starčeviću (1992. – 2007.), Tonćiju Pruscu (2007. – 2011.) i Zoranu Juraju Sabljaku (2011. – danas), koji će i dalje biti vodeći u digitalnoj eri.

Govoriti o ovim urednicima bez hvale znači pustiti da su njihova djela dovoljna. Ipak, posebno priznanje zaslužuje T. Starčević, čiji je mandat bio najdulji. Od samog početka, sa stoičkom odlučnošću koja je simbolizirala njegov karakter, nadgledao je svaki aspekt publikacije - osobito studentske stranice i kasnije dodatak New Generation - sve do svoje smrti. Njegova ostavština ostaje kao kamen temeljac u sjećanju svih vezanih uz Vjesnik, pa i onih koji su mu se našli na putu.

On ostaje kao temeljna figura u sjećanjima svih vezanih uz Vjesnik, pa i onih koji su mu se našli na putu. Tijekom četiri desetljeća, nebrojeni predani suradnici – na svim meridijanima gdje žive Hrvati – pridonijeli su ovom pothvatu. Među njima, neumorna Suzana Fantov zaslužuje posebno priznanje za svoje neprestano inventivno novinarstvo i nepokolebljivu domoljubnu predanost.

Odajući priznanje za nepokolebljivo služenje Vjesniku, posebno treba istaknuti Nikolu Rašića iz Posavlja i Mate Bašića, Zagrepčanina iz Imotskoga, koji su svoju stručnost dosljedno davali tijekom mandata posljednja tri urednika.

Iako se ovaj izvještaj dotaknuo Vjesnikovog višestranog podrijetla - njegove ideološke i operativne zamršenosti - vrijedi ponoviti da ti napori nisu bili bez poteškoća. Takav pothvat zahtijevao je vizionarsko vodstvo da uskladi ove složenosti, upravlja izazovima i razotkrije neprijateljske, subverzivne planove. Gledajući unatrag, nedvosmisleno je jasno da je ta uloga pripala dvojici: duhovnom voditelju vlč Josipu Kasiću i Zdenku Marinčiću, tada relativno mladom, ali revolucionarno oštroumnom administrativnom ravnatelju.

Naposljetku, osim pohvala i neizrečenih kušnji, pažljivi analitičar društvenih nastojanja – posebice operacija medija – mogao bi se razumno zapitati: kako je Vjesnik upravljao financijskim turbulencijama izazvanim COVID-19, s obzirom na strogu australsku politiku protiv pandemije?

Dok mnogi Hrvati šetaju središnjim distriktom Melbournea, pogled će im se neizbježno zadržati na istaknutom natpisu 'I&D Group' koji krasi jednu višekatnicu. Oni koji poznaju ime, a takvih je mnogo, nasmiješit će se i s odobravanjem primijetiti: "Prekrasno! Još jedna znamenitost koju su iskovali Ivan i Kathy Filipović."

Jednostavnije rečeno, Hrvatski vjesnik vjerojatno bi posrnuo tijekom pandemije COVID-19, razdoblja u kojem su se borile čak i renomirane svjetske publikacije. Ipak, Ivan je, vođen svojim dubokim hrvatskim identitetom i domoljubljem, osigurao njezin opstanak. Prepoznao je nezamjenjivu vrijednost očuvanja jedine hrvatske novine u Australiji — žive niti koja povezuje napore dijaspore u Australiji i Europi s povijesnom borbom Hrvatske za državnost.

Doprinosi ove izvanredne obitelji sežu daleko izvan Heralda . Ustrajno podupiru hrvatske kulturne, dobrotvorne i sportske organizacije diljem Australije. Takva predanost zaslužuje, u najmanju ruku, formalnu pohvalu zagrebačkih ministarstava i institucija nadležnih za Hrvate izvan domovine.

Ivan i Kate — hrvatski domoljubi — namjerno su usmjerili svoja sredstva u očuvanje hrvatske baštine. S guštom se bore za sportska društva, ali njihova je odlučnost još žešća u očuvanju pisane hrvatske riječi. Od 2018. održavaju tjednik, shvaćajući njegovu kulturološku težinu. Takva je postojanost svojstvena njihovom karakteru; ne čudi što Ivan, kao predsjednik Uprave i direktor Vjesnika , sada pozorno nadzire njegovu digitalnu evoluciju.

Naša srca prepuna su zahvalnosti; neka se njihovo buduće putovanje nastavi sa svrhom i dubokim utjecajem.

Što je pratilo Tita?

Kao što povijest pripovijeda, Moskva je - posebno pod Brežnjevom - ugušila 'Praško proljeće' 1968. tenkovima. Slično je 'Hrvatsko proljeće' brutalno ugušeno od strane Beograda (točnije Tita) krajem 1971. godine, ostavivši desetke tisuća Hrvata progonjenih, profesionalno marginaliziranih, a stotine zatvorenih.

Pokušaj ustanka Hrvatskog revolucionarnog bratstva, kodnog naziva Operacija Feniks (ili Bugojanska grupa ), u lipnju i srpnju 1972. doživio je neuspjeh. Površno – i kroz nemilosrdnu propagandu – činilo se da je svaki otpor ugašen unutar komunističkog konstrukta Jugoslavije.

Ipak, povijest nas uči, kao što je zabilježeno još u antici, da šutnja krije prkos. Kao što je Mirabeau, čelnik francuske Nacionalne skupštine, izjavio nakon juriša na Bastillu: "Šutnja naroda služi kao upozorenje monarsima." Unatoč režimskoj propagandnoj mašineriji, mlađe hrvatske političke frakcije tiho su održavale revolucionarne napore unutar domovine.

Ova šutnja, poput one upućene Luju XVI., nosila je snažnu poruku. Egzodus revolucionara poput Brune Bušića i kasnije Stjepana Đurekovića — bivšeg direktora Ine — katalizirao je radikalniju putanju u inozemstvo. Svojim pisanjem i aktivizmom te su osobe razotkrivale političku i gospodarsku stvarnost Jugoslavije, potičući neslaganje.

Tito, ostario i boležljiv, umro je u svibnju 1980. u 88. godini. Komunistička partija, osnažena stranom financijskom potporom, orkestriranim propagandnim kampanjama i upadljivim okupljanjem zapadnih političkih ličnosti na njegovu razmetljivom državnom sprovodu, nastojala je projicirati sliku nepokolebljive snage. Ipak, ti napori nisu mogli prikriti izvještačenost i krhkost jugoslavenske federacije.

Prisutni su u Beograd stigli zaokupljeni jedinstvenim pitanjem: Što će slijediti Tita? Predviđanja o eskalaciji previranja ubrzo su se ostvarila. Srpski nacionalistički skupovi su porasli, potaknuti retorikom koja je Srbe prikazivala kao žrtve izrabljivanja. Kao odgovor, otpor je pojačan u Hrvatskoj i Sloveniji, otkrivajući pukotine koje su se širile jugoslavenskim komunističkim režimom.

Do ranih 1980-ih, prodemokratski pokreti u Poljskoj signalizirali su širu ideološku krizu koja je zahvatila istočnu Europu, uključujući SSSR. Iako to zahtijeva vlastitu analizu, ti su pomaci – zajedno sa sve manjom zapadnom pomoći i gospodarskim propadanjem Jugoslavije – ubrzali raspad socijalističke države.

Tijekom desetljeća mnogi su politički emigranti predviđali raspad jugoslavenskog entiteta godinama prije 1990. Ipak, kada je ta godina stigla, dugo očekivani trenutak hrvatske euforije i slavlja konačno je bio nadohvat ruke.

Dan neovisnosti

Nakon sloma socijalističkog vodstva u Beogradu, u Republici Hrvatskoj brzo je uvedena višestranačka demokracija. Na parlamentarnim izborima, koji su održani 22. travnja, a drugi krug održan 6. svibnja, Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (HDZ) odnijela je odlučujuću pobjedu osvojivši 205 od 351 mjesta.

Osnivačka sjednica ovog demokratski izabranog Sabora održana je 30. svibnja — datum koji se danas obilježava kao Dan neovisnosti, simbolizirajući politički preporod Hrvatske. Ipak, dugotrajno postojanje Jugoslavije značilo je da bi prekid veza s tim navodnim “bratstvom naroda” zahtijevao težak danak, plaćen krvoprolićem i ekonomskim razaranjem.

Tragično, Hrvatska je pretrpjela godine zločina i širokog razaranja pod napadima velikosrpskih paravojnih postrojbi i Jugoslavenske narodne armije. Sve do vojno-pohodne operacije Oluja ne bi stiglo oslobođenje. Hrvatske su snage vodile mukotrpnu i neravnopravnu borbu, ovjekovječenu kao Domovinski rat, za obranu svoje tek nastajale suverenosti.

Dijaspora i domovina

Naravno, hrvatsko iseljeništvo svesrdno je podržalo prve demokratske izbore u zemlji i dalo znatnu pomoć tijekom Domovinskog rata, koji je presudno prekinuo pravne veze s Jugoslavijom. Ipak, odnos dijaspore i domovine bio je narušen pogrešnim potezima čiji odjeci traju i danas.

Među njima je i nagli pad brojnih izdanja dijaspore u prvim mjesecima novonastale Republike Hrvatske. Uzeli su maha pogrešni narativi, odbacujući politički konzervativne emigrantske medije kao zastarjele ili čak štetne. Pojavile su se tvrdnje da će te novine potisnuti – kvalitativno, društveno i politički – hrvatski domaći tisak. Takva su se stajališta zgodno uskladila s prioritetima prvog vala neiskusnih diplomata u zemlji, od kojih su mnogi pokazali malo interesa za očuvanje kulturne i institucionalne ostavštine dijaspore.

Zašto je Hrvatski vjesnik izbjegao tu sudbinu? Odgovor leži u njezinim ključnim kadrovima koji su retoriku pretvorili u djelo. Mnogi iz Vjesnika i Uzdanice bili su među prvima koji su se vratili u Hrvatsku, stvarajući most suradnje između Australije i domovine. Udubljeni u ratne borbe Republike – sudjelovanje u Domovinskom ratu i naporima civilne obrane – stekli su iz prve ruke uvid u potrebe nacije. Ta im je blizina omogućila da razaznaju, ispred ostalih skupina dijaspore, koji će se doprinosi pokazati uistinu vrijednima.

Uredništvo Domovine

Drugi, još razorniji udarac izdanjima iz dijaspore – osobito u inozemstvu – došao je s brzim usponom digitalne tehnologije. Ipak, mlađe uredništvo Hrvatskog vjesnika predvidjelo je i rizike i prilike ove promjene.

Godine 2013. iskusni urednik Zoran Sabljak i nepokolebljivi stup Stanko Kovač (poznat kao “Canberran”) otputovali su u Hrvatsku. Nakon ponovnog povezivanja s domovinom, prednjače osnivanje domaće redakcije. U suradnji s Vesom Jurićem i Ivom Butkovićem iz zagrebačke mreže Uzdanica izradili su detaljan nacrt za implementaciju.

Mjesecima kasnije pokrenuta je zagrebačka redakcija koja je uspostavila dinamično partnerstvo sa svojim australskim kolegom. Novinarski veterani Marko Barišić i Božo Čubelić , zajedno s Vesom Jurićem , preuzeli su odgovornost za njezino djelovanje – uspješan model koji traje i danas i obećava oblikovanje budućih inicijativa. Ovo ostaje jedini (i ogledni) primjer održive sinergije domovine i dijaspore u tiskanom novinarstvu.

Neupitno je da je nepokolebljivo zalaganje Hrvatskog vjesnika za hrvatska načela značajno unaprijedilo državotvornost i slobodu nacije, pokazujući snagu organizirane dijaspore. To se nasljeđe ogleda u bezbrojnim globalnim naporima, posebice u kritičnoj potpori dijaspore tijekom Domovinskog rata.

Kako bismo izbjegli svođenje ovog prikaza na puku anegdotu, u nastavku navodimo ključne inicijative, potkrijepljene pojedincima koji su ih vozili.

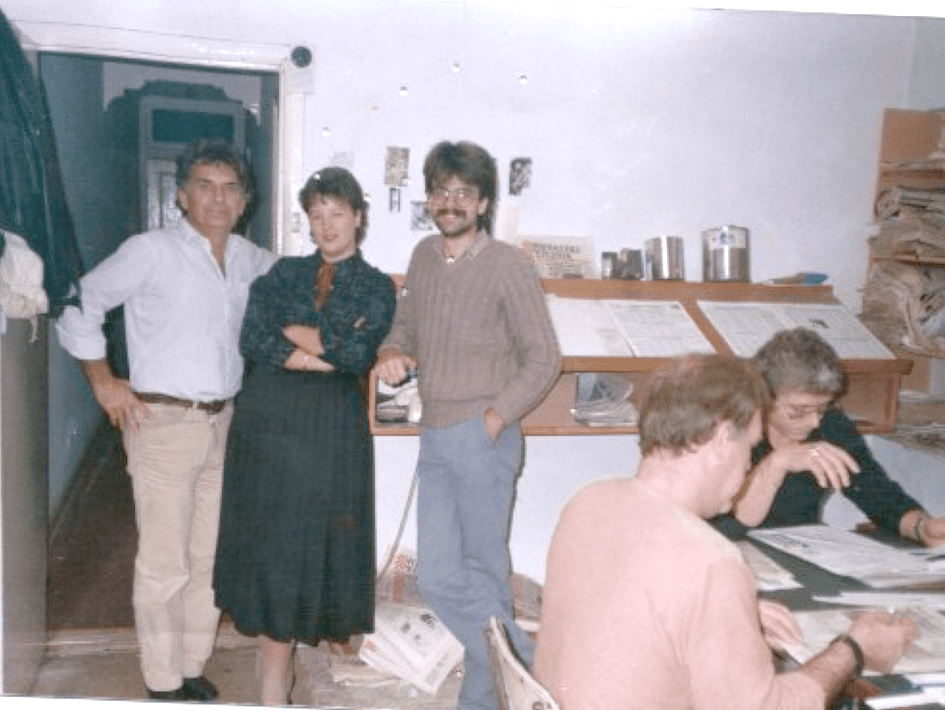

Još u proljeće 1990., kad je nada prvi put sinula na hrvatskom horizontu, djelatnici Hrvatskog vjesnika sa studentskog odjela – Veso Jurić , Beta Gal i Snježana Krpan – otputovali su u Hrvatsku. Po dolasku surađivali su sa zagrebačkom mladeži u pokretu 'Baraka', aktivno podupirući predizbornu kampanju HDZ-a. Njihove su depeše Heraldu donosile novosti iz domovine u stvarnom vremenu.

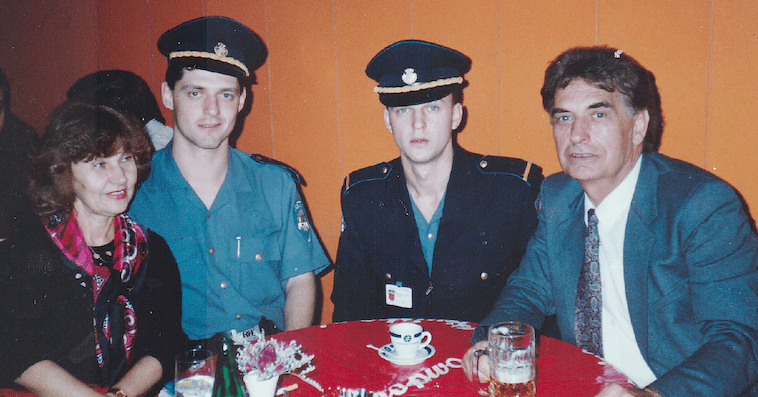

U travnju 1990. održani su prvi parlamentarni izbori u Hrvatskoj. U lipnju se tom pionirskom trojcu pridružio urednik Glasnika Ivo Butković . Sljedećeg mjeseca, čarter letom iz Australije stigli su članovi nogometnog kluba NK 'Croatia' Sydney-Melbourne i njihovi navijači—što je označilo jednu od najranijih sportskih razmjena između dijaspore i domovine.

U kolovozu 1990. u Zagreb stiže još jedna grupa iz Melbournea, među kojima su suradnici Glasnika i članovi Uzdanice: Anđelka Stojić (danas profesorica engleskog u Mostaru), Slavica Butković , Zdenko Marinčić i Nikola Vrselja . Uz četvoricu domaćih suradnika, nazočili su 18. kolovoza Osnivačkom saboru HDZ-a BiH u Sarajevu. Odatle su ispratili Marinčića u Čitluk — njegov prvi povratak kući nakon desetljeća u inozemstvu. Sljedećeg dana svjedočili su osnivačkoj skupštini HDZ-a u Ljubuškom, gdje su se tisuće ljudi okupile na nogometnom igralištu—zapanjujući prizor za one koji prvi put dolaze u Hercegovinu.

Po povratku u Zagreb, ovi su iseljenici svoja iskustva i fotografije podijelili s Glasnikom , čime je novina učvrstila ulogu vitalnog mosta između Hrvatske i dijaspore.

Godine 1991., premještajem urednika Butkovića na bojišnicu u Osijek i Laslovo, Glasnik postaje jedini iseljenički list koji je opsežno pratio vukovarsku krizu i istočnu bojišnicu. Tome je pridonio Mirko Volarević , ravnatelj osječkog 'Informativnog centra' (kasnije konzul u Sydneyu i Perthu).

Iste godine sedmorica dragovoljaca iz Geelonga, nazvanih 'the lads', uz seniore Jerka Kovača (Canberra) i Slavka Ćuka (Melbourne), pridružili su se osječkoj bojišnici. Među njima je bila i Željka Jukić , tada daktilografica Heralda , a danas profesorica engleskog jezika. Vratio se i Tomislav Bošnjak , bivši tajnik 'Uzdanice' i Hrvatskog narodnog vijeća. Neumoran zagovornik misije lista, kasnije se istaknuo kao diplomat u arapskim državama, Izraelu i trenutno Egiptu.

Marijan Gubić , Starčevićev suradnik tijekom studentskih godina, stigao je 1991. Nakon službe u Ministarstvu vanjskih poslova, predstavljao je Hrvatsku na više američkih dužnosti prije nego što se vratio u Melbourne. Vice Skračić , podrijetlom iz Južne Australije, prošao je sličan put – služeći u SAD-u, a sada kao veleposlanik u Kanadi. Još kao student promovirao je Glasnik uz svoje roditelje Ivana i Jasnu Skračić — istaknute čelnike Uzdanice u Australiji.

Ovaj prikaz ističe samo djelić mreže Hrvatskog vjesnika – pojedince čiji napori tijekom Domovinskog rata i demokratske tranzicije Hrvatske predstavljaju primjer trajne predanosti dijaspore slobodi.